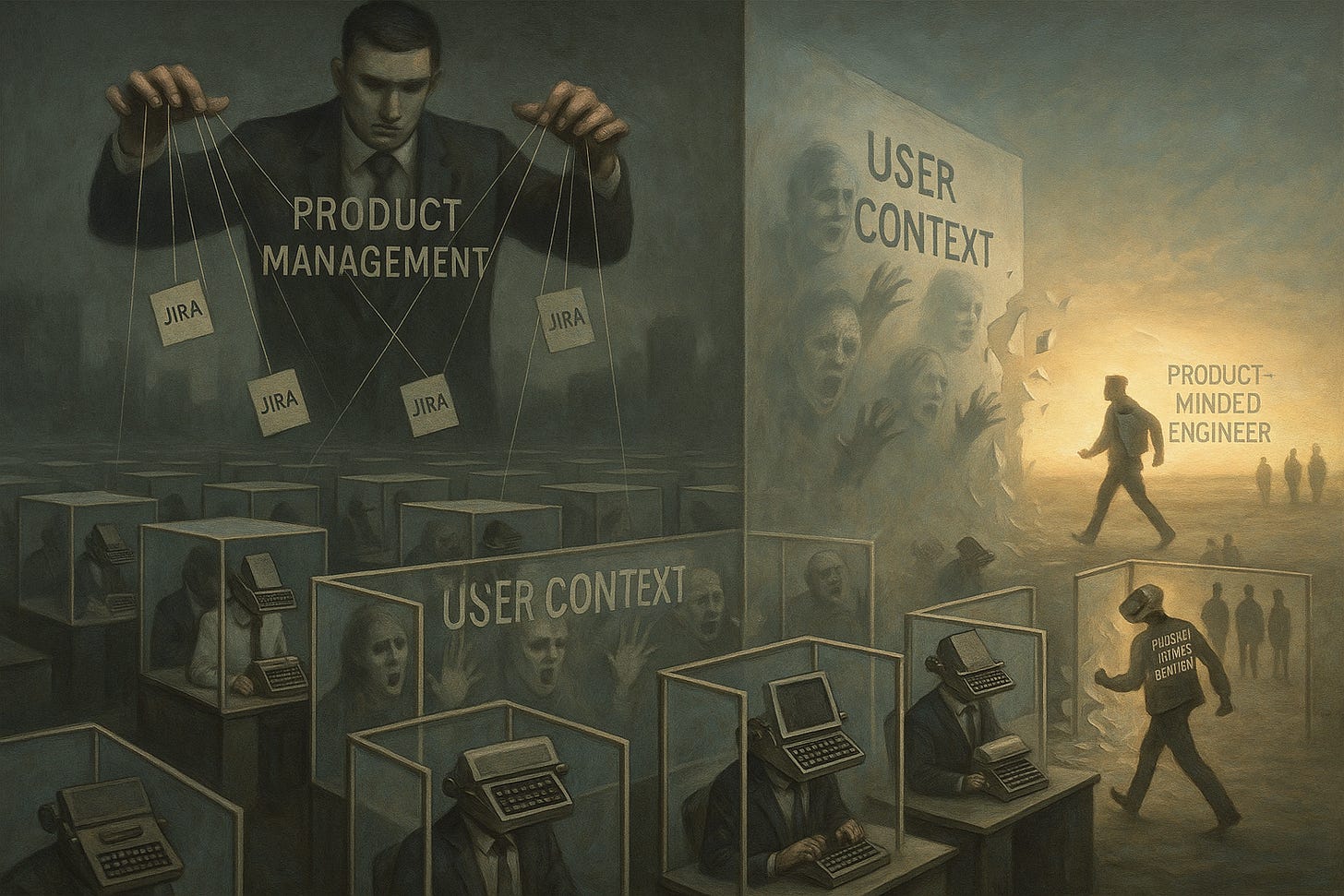

In the grand theatre of modern software development, a psychological operation of immense scale and success is being waged. It is a campaign so effective that its subjects - talented, intelligent software developers - willingly participate in their own intellectual neutering, all under the guise of “efficiency,” “focus,” and “strategy.” This PsyOp is the discipline of product management. Born from a desire to bridge the gap between business and technology, it has metastasised into a function that often creates the very problems it purports to solve: it establishes an unnecessary and lossy intermediary, silos critical knowledge into a single point of failure, and systematically reduces the role of the developer from a creative problem-solver to a glorified typist - a “code monkey” in a comfortable chair.

The foundational deception of product management lies in its positioning as the essential translator between the customer and the developer. The narrative is compelling: the Product Manager (PM) ventures into the wild, gathering the precious, esoteric needs of the user. They then return to the engineering tribe, translating these needs into perfectly formed, digestible units of work — the user story. This process, we are told, shields developers from the chaos of customer feedback, the ambiguity of business goals, and the distraction of stakeholder politics, allowing them to focus on their "true craft": writing code.

This narrative is a dangerous fiction. The PM is not a perfect, lossless conduit; they are a human filter, complete with their own biases, interpretations, and ambitions. Every conversation they have, every piece of feedback they receive, is compressed and re-interpreted. The rich context, the emotional undertone of a user’s frustration, the subtle hesitation that hints at a deeper, unarticulated problem - all of it - is flattened into the sterile, two-dimensional format of a Jira ticket. This game of telephone guarantees that the developer, the person actually building the solution, is working with a degraded, second-hand understanding of the problem. A developer who speaks directly to a frustrated customer might realise the request for a “CSV export button” is a cry for help to automate a painful manual data entry process into another system. The developer might then propose a direct API integration, a far superior solution that eliminates the root problem. The PM, focused on a clean backlog and delivering on the explicit request, might simply write the ticket for the button, condemning the user to a slightly more convenient version of their existing pain and preventing a truly innovative solution from ever being conceived. The PM, in this structure, becomes not a bridge but a gatekeeper to empathy.

This leads to the second, more insidious effect: the institutionalisation of knowledge silos. The modern organisation, in its infinite wisdom, has decided that the “what” and the “why” belong exclusively to the PM, while the “how” belongs to engineering. This creates a centralised node of failure. The PM becomes the sole proprietor of product vision and customer intimacy. The roadmap, the market analysis, the competitive landscape - this critical information is hoarded, either intentionally to protect status or unintentionally as a byproduct of the role’s design. The team’s collective intelligence is actively suppressed. Instead of a group of brilliant minds collaboratively dissecting a business problem, you have a queue of specialists waiting for their next instruction.

This model is not just inefficient; it is dangerously fragile. When the PM goes on vacation, the team’s ability to make informed decisions grinds to a halt. When the PM leaves the company, they take the product’s soul with them, leaving the team as functional orphans, capable of maintaining the old but incapable of birthing the new. The illusion sold to the business is one of clarity and a single source of truth. The reality is a high-risk dependency on one individual, creating a “bus factor” of one for the entire product’s strategic direction. The team is told they are “empowered,” yet their access to the primary sources of information is throttled, fostering a culture of dependency, not ownership.

The final and most corrosive outcome of this PsyOp is the systematic transformation of developers into code monkeys. By separating problem discovery from solution implementation, the role of the developer is hollowed out. Their most valuable asset —the analytical, systems-thinking mind capable of deconstructing complex problems and modelling elegant solutions — is relegated to the mechanical task of translating pre-digested requirements into syntax. This is the modern-day Taylorism of knowledge work, breaking down a creative and intellectual process into a predictable, repeatable, and soul-crushing assembly line.

The phrase “We just need to be more like a feature factory” is uttered in boardrooms without a hint of irony, celebrating the very dehumanisation of the craft. Developers, who are often drawn to the field by a passion for building and a love of complex problem-solving, find themselves in an intellectual straitjacket. Their engagement plummets. Why bother thinking deeply about the business impact when your job is simply to close the ticket? Why challenge a requirement when you lack the customer context to offer a meaningful alternative? This process not only leads to disengaged employees and higher attrition but also to inferior products. The best technical solutions are born from a deep, holistic understanding of the problem space. When the person with the deepest technical knowledge is divorced from the problem, the solution will inevitably be suboptimal.

To be clear, the villain is not the individual Product Manager, many of whom are smart, dedicated people struggling within a broken system. The villain is the system itself - a system that, in its quest for order and predictability, has created a rigid caste system in software development. The promise was synergy; the reality is segregation.

The antidote to this grand deception is not the elimination of product thinking, but its radical decentralisation. It is the cultivation of “product-minded engineers” who are not only permitted but expected to engage directly with customers. It is the fostering of teams that share ownership of the “what” and the “why,” not just the “how.” In this model, the “product” role, if it exists at all, transforms from a gatekeeper to a facilitator - a coach who helps the team hone its customer-facing skills, a strategist who provides market context as a service to the team, not as a directive from a throne.

The software industry stands at a crossroads. It can continue down the path of the PsyOp, building ever more elaborate processes and frameworks that entrench the PM as the central puppet master, turning development teams into efficient but uninspired marionettes. Or, it can choose a different path: one that recognises that the people closest to the technology, when armed with direct customer context, are best equipped to create the future. The first step is to see the PsyOp for what it is: a comforting illusion of control that is stifling the very innovation it claims to enable. The goal is not to fire all the PMs; it is to liberate their function and distribute it to those who can wield it most powerfully: the makers themselves.